Effective Daylighting Workflows for LEED v4

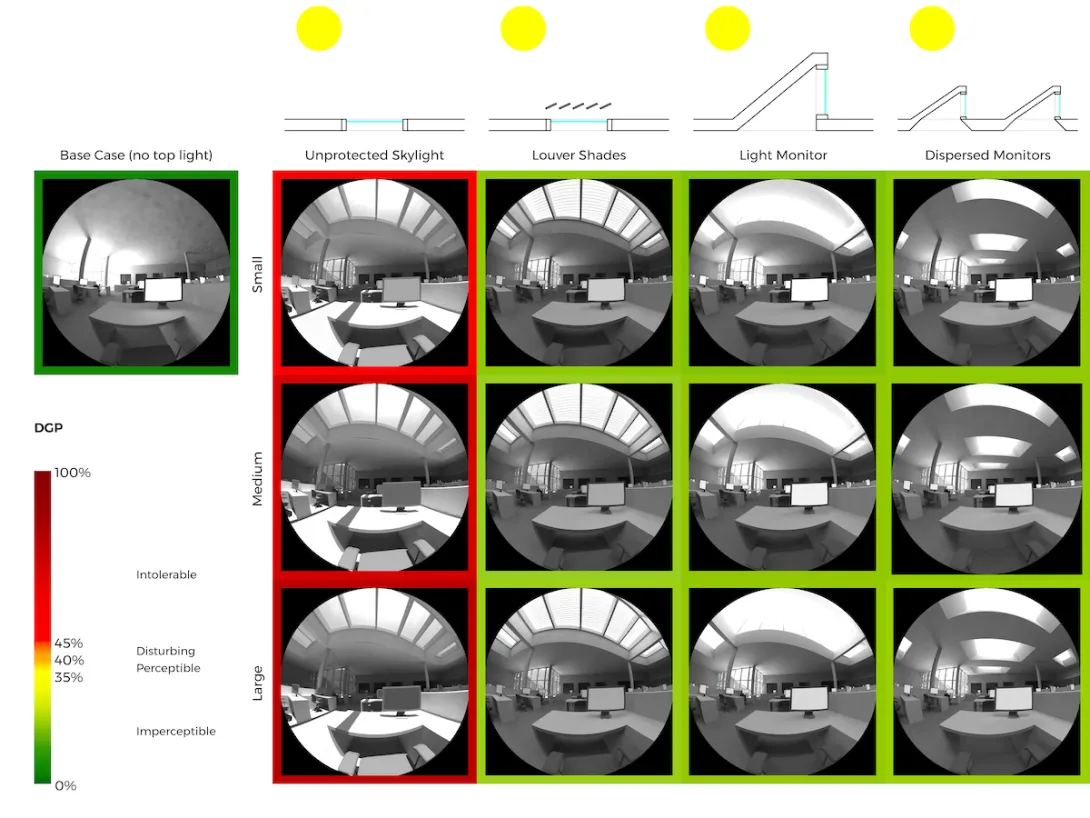

This glare matrix shows the results of computational design scripting, which allowed designers to simultaneously compare multiple types of toplighting for daylight, glare, and energy implications.

There is a mountain of research to support the positive impacts of good daylighting, but there is less guidance on how to do it well. In this blog post and in a related webinar, we’ll look at how LEED v4 is changing that and touch on a new tool—computational design—that helps make the process of designing for daylight and quality views not only faster but also more successful.

LEED v4 was a revolution

Since LEED v4 came out, there has been an increasing level of sophistication when it comes to understanding what makes for good daylight. Balancing the metrics of spatial daylight autonomy (sDA) and Annual Sunlight Exposure (ASE) has created an awareness that there is a sweet spot in design that maximizes daylight access while avoiding direct sun and the associated risks of visual discomfort (although the release of v4.1 effectively deemphasizes the glare requirements and encourages more projects to pursue increasing daylight in spaces, as measured by sDA).

Similarly, the LEED v4 Quality Views credit pushes designers to think beyond providing a minimal line of sight to a window and to move toward improving angles of view and connecting occupants with visual access to natural elements.

But for projects not pursuing LEED, or for those LEED projects that don’t have the time to do early-phase daylight modeling, the default process is to use rules of thumb and designer’s intuition for shaping the building and facades in order to bring in daylight. Without quantification, however, this approach can result in wishful thinking that ignores critical factors such as climate and site characteristics, façade orientation, or interior layout or materials.

Modeling now the norm

Fortunately for projects pursuing LEED v4, daylight modeling has become the standard for daylight design, providing an accurate assessment of the daylight performance of any conceivable design. Annual daylight simulation takes into account the climate-specific variability in sky conditions hourly and therefore the predicted amount of light available at any time throughout the year. The model incorporates the surrounding context so that the effects of adjacent buildings and trees on daylight levels can be properly accounted for.

With modeling, the specific façade configuration can be reflected in the analysis, however unique it may be. The visual light transmittance of the glazing product used can be described, and optically complex materials such a translucent or fritted glass can be accurately modeled. Dynamic systems such as electrochromic glass or automated shading can also be incorporated into the simulation to understand how the operation of those systems in relationship to solar conditions and occupant preferences will affect overall daylight performance at every hour of the year.

Smoothing workflow speed bumps with computational design

However, as with energy modeling, daylight simulation often takes place too slowly and too reactively, waiting for a fairly well defined design to be performed on and looking at a limited number of alternative configurations. This workflow requires a delay in proposing changes, testing those changes in the model, discussing and digesting those changes with the design team, and then iterating forward.

The answer to this problem lies in the emerging field of computational design, where existing architectural tools like Rhino can utilize computer scripting to generate and flexibly update geometry.

The open-source nature of the platform also lends itself to live connections to validated analytic engines such as Radiance. The combination of these two factors means that studies can be programmed to automatically run a vast spectrum of possible design scenarios that returns a quantitative foundation for design decision-making using the metrics of sDA, ASE, or any other that the team feels is appropriate.

Design elements that we typically parameterize (define and then subject to side-by-side comparisons) include:

- floor plate depth

- size and location of fenestration

- shading elements

- the optical properties (reflectivity and transparency) of materials

The fluidity of the model allows us to nimbly evaluate many more combinations of variables to help designers identify solutions that simultaneously meet their aesthetic, programmatic, and daylight objectives. Custom scripting in languages such as Grasshopper or Python can respond to project-specific design investigations starting at the earliest concept phase and continue through more detailed analysis in subsequent phases.

Dynamically defining quality views

Computer scripting can also help analyze and document the LEED Quality Views credit by evaluating vantage points for the four different view types in the credit much faster and with more precision than if done manually. This gives the design team the opportunity to evaluate and incorporate feedback from the analysis multiple times before their design is finalized.

Overall, the computational design process provides significantly more timely and proactive feedback during the design process than the traditional daylight modeling methods while shifting the effort for the designers to tasks that will provide greater value, such as the analysis of multiple variables. Our webinar will focus on how computer scripting has been applied to projects to provide design exploration for daylight and views as well as facilitate document for LEED compliance.

In addition, the same process can be used to evaluate building energy use and loads, which we will discuss in a follow-up blog post and as part two of the webinar series.