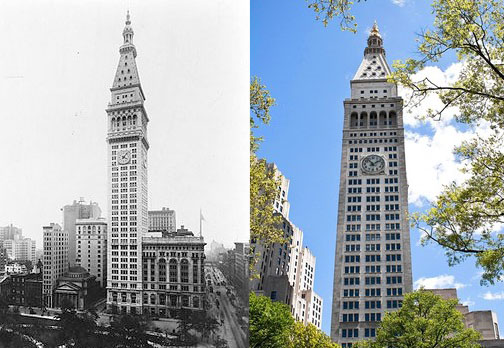

The LEED-certified New York Edition Hotel chose to refurbish the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company building, a National Historic Landmark, preserving cultural value and embodied resources.

Big Picture

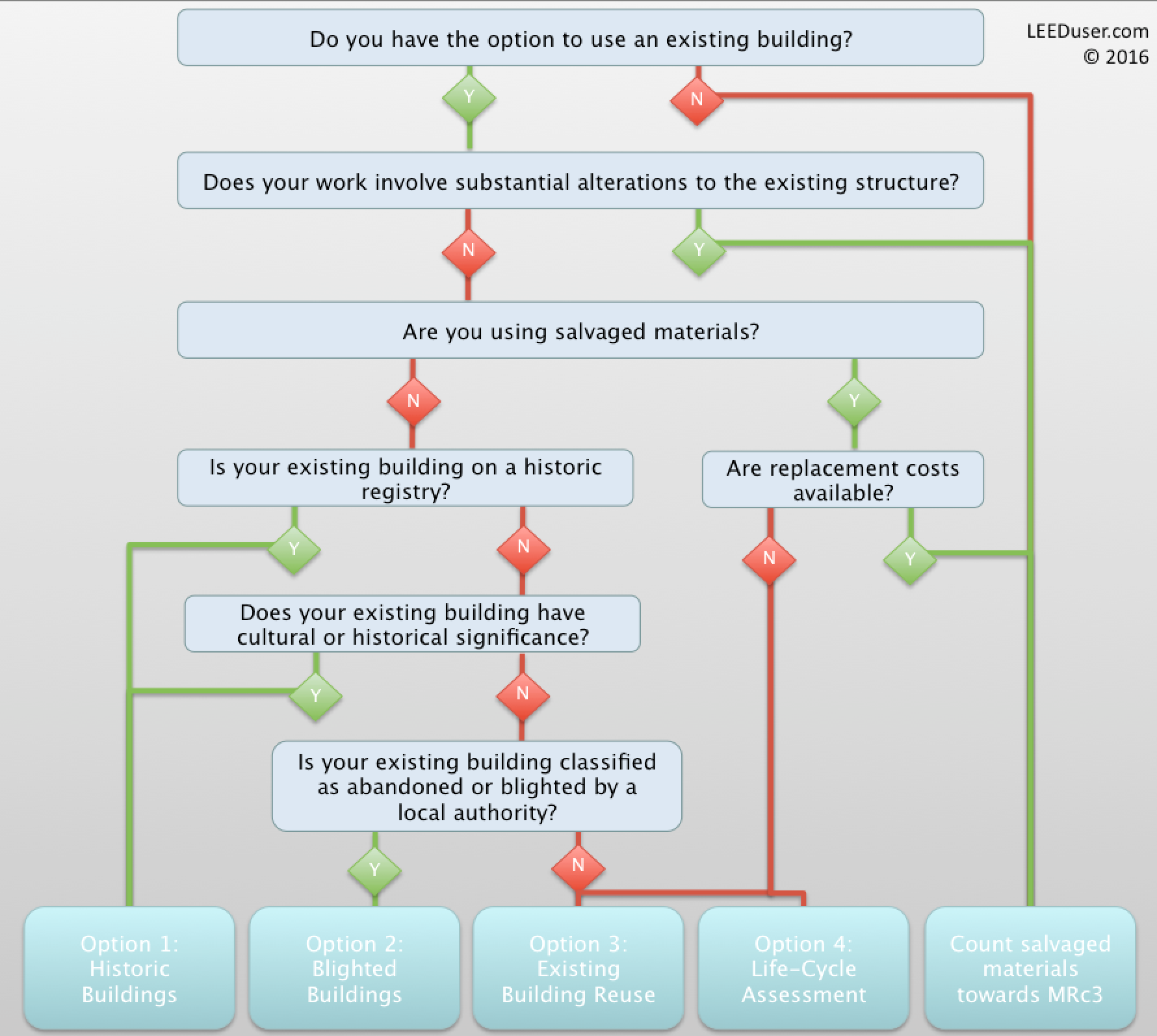

LEED v4 Options 1 and 2 for reusing historic, blighted, or abandoned buildings in have been eliminated in V4.1. Instead the new Option 1 for Building and Materials Reuse allows teams to exclude structurally unsound portions of the building deemed historic, blighted, or abandoned, and all five points are available to the project at the 75% building threshold.

Option 2 for new construction breaks the Whole Building LCA path into tiers that allow project teams to access one point just for doing an assessment and additional points for achieving reductions. This that project teams can dip a toe into LCA without fully committing to a comparative assessment. It also means that for teams that fully commit, one point is guaranteed even if the project doesn’t achieve embodied impact reductions.

The Details

Option 1. Building and Material Reuse

We are assuming the calculation method is still based on surface area, same as in v4, since there is no reference guide language to contradict this. Like the v4 options, this option in v4.1 combines exterior and interior elements, this time as two paths, one for exterior and one for interior, then can be combined for a total of five points for BD+C projects.

For these options, compliance is based on the percentage of surface area that’s being reused or preserved. Both exterior and permanently installed interior elements should be included in these calculations, including the surface area of up to three separate layers in each assembly.

For example, if you keep a brick wall but replace the drywall on the inside face, you’ll still get partial credit for preserving the assembly. If there are more than three layers, you can even pick which three to include. However, one layer must be structural, and the other two layers must be interior and exterior finishes.

The point thresholds for exterior elements have been lowered to give points for as little as 15% building reuse, as opposed to the minimum 25% in v4. This makes this credit more accessible to proejcts reusing a small portion of a building or renovating a building that has structural issues.

What’s excluded?

The maximum amount of a building than can be excluded has been removed. Hazardous materials can also be excluded. If you remove a layer of an assembly and don’t replace it, you can exclude that layer from the calculations since you haven’t created a demand for new materials. Lastly, window assemblies are excluded from credit calculations, so you won’t be penalized for upgrading to more-energy-efficient frames.

Look out for salvaged materials

Salvaged materials from both on and off the project site can contribute to reuse calculations. This provides a path to claim the environmental benefits of the reused materials if it’s too difficult to estimate replacement costs for MRc3: Sourcing of Raw Materials. However, salvaged materials are only significant in the calculations if they replace an existing material—in which case the salvaged layer gets counted as reused. If it’s a newly added layer, then it has a neutral impact in the calculations, so it’s not possible to achieve this credit through adding salvaged materials alone.

Option 2: Life-cycle Assessment

Option 2: Whole-Building LCA, now has several additional paths. Two of these new paths are stepping stones, creating an easier entry point for those encountering whole-building LCA for the first time. There is also a new Path 4 that assigns the most points (four) to a solution that offers the most significant reduction in embodied carbon.

Life-cycle assessment (LCA), as it applies to buildings pursuing LEED, involves creating an inventory of the environmental impacts associated with building materials’ manufacture, transportation, use, and disposal. Think of it as a life-cycle cost estimate, only in this case the “costs” are metrics in key environmental impact areas (called “indicators” in LCA terminology). Commonly used LCA indicators represent atmospheric impacts, fossil-fuel resource depletion, and some ecological effects.

LCA is intended to be an iterative modeling tool that informs decisions during the design process, much like an energy model. It’s a time-intensive process, but if it’s set up to support broader project goals and not just the LEED credit, LCA can be a rewarding way to validate sustainability strategies that are otherwise hard to assess.

How you use the LCA will likely depend on when the process begins relative to design decisions, the context of your project, owner commitment, and the time and resources available to updating the model. Committing to using LCA as a tool throughout the design process will reduce the risk of missing targets and can help you get the most value from the process.

First, define your goals

To achieve higher point thresholds in this credit, your project must demonstrate reduction in global warming potential and at least two of the five other basic indicators (ozone depletion potential, acidification, eutrophication, tropospheric ozone formation, and non-renewable energy resource depletion). Since many choices may have tradeoffs in environmental impacts, decide early in the process which indicators you want to prioritize.

Next, think carefully about which elements have the most influence over your project’s life cycle impacts, and which areas you have the most control over. This credit specifically excludes all MEP equipment and operating energy, so it’s all down to design optimization and material selection.

For a newly constructed building, there might be a few specific materials that provide opportunities: maybe all the glass on the market turns out to be essentially the same in terms of environmental impacts, but you have control over selecting a locally made concrete with high fly ash content.

Items such as interior finishes and furniture are optional, but don’t plan to spend too much time over details in your LCA that have small effects on life-cycle impact reductions. These items should really only be included when other opportunities are limited, or if the LCA is going to help inform selection of a particular type of product.

Select an LCA tool

There are many different databases and public LCA tools out there. Some are free, some aren’t, some are easy, some are complex, and some even integrate with existing design software. It’s important to find a tool that aligns with your experience level and will provide the right information to document this credit. Start by asking the following questions:

Is the tool recommended specifically for evaluating buildings?

Does it follow standard methodologies? Look for ISO 14044 and ISO 21930 or EN-15804.

Does it measure the six basic indicators required for LEED compliance (global warming potential, ozone depletion potential, acidification, eutrophication, tropospheric ozone formation, and non-renewable energy resource depletion), and any others that are important to my goals?

Does the tool’s database cover my project’s region?

Does it allow for custom inputs if I want to include a specific product?

Will the inputs be easy for me to calculate and update as I go?

Define your baseline

Just like an energy model, the results of an LCA only make sense as a comparison against a baseline. However, unlike an energy model, there are no hard-and-fast requirements for what should be included in that baseline.

The LEED Reference Guide provides some specific requirements for the baseline that are designed to create one that is “functionally equivalent” to the proposed case. In other words, the baseline should meet the project brief and any regulatory requirements, and have the same gross floor area, program, and location as the proposed building. It should also use assemblies that can meet the insulation requirements of EAp2: Minimum Energy Performance (don’t forget, in this case the minimum energy performance required by LEED certification is another functional requirement!). Lastly, the source, quality, and precision of the data should be the same in each case to create a valid comparison.

Outside of that guidance, the requirements are vague because what defines an appropriate baseline really depends on the project’s context and goals. It is critical to begin the LCA with a clear understanding of what you’re comparing your project against and how that comparison will drive design decisions, as well as what design variables will be in play.

Refine and assess until goals are met

Use the LCA as a tool to evaluate potential major decisions, and weigh the change to each of the six indicators against other considerations (such as energy consumption, cost, or availability).

Start with an early conceptual model and include major structural and envelope components, even if generic. The results of this early model may not match your final design, but it’ll provide the relative contributions of each material to the building’s overall impacts and tell you where the best opportunities are for further reduction—and where not to spend too much effort on alternatives. For example, window assemblies might have high embodied energy, but if your building’s window-to-wall ratio will only be 15%, then it will make more sense to focus on the wall assemblies instead.

If LCA is pursued early enough, compare the LCA impacts associated with potential structures and surface-area-to-volume ratios of different massing options. These very early decisions tend to provide the greatest opportunity for reducing LCA impacts though reducing overall material needs. In later phases, the effects of each remaining decision typically diminish, making it difficult or impossible to achieve the required reduction at the very end of the design process.

Updating the LCA model as you go

As the design progresses and becomes more detailed, the LCA should get more detailed as well.

Continue to update the model and track how the impacts change relative to the original results, until the project’s goals are met.

Example 1. A new building is built on an open lot with plenty of room. The project team is interested in how changing the form will affect the amount of material required, and in turn the life-cycle impacts. They create a baseline shape that’s a generic rectangle and compare other massing strategies with the same total area against it to see if they can reduce the structural and envelope impacts.

Example 2. A new building is built in a confined urban lot with strict zoning requirements that determine the massing. The team decides that the biggest impact is in their material selection. They look at other new buildings in the area to come up with a baseline material palette. After creating a baseline that’s the same shape as the proposed building, they compare the life-cycle impacts of façade options and select the one with the greatest reduction in global warming potential.

Should I Upgrade?

This credit is simpler and newly includes “baby steps” under the WBLCA option, so upgrading is likely to work well for many projects.