“Anyone else finding a trend of clients wanting LEED-certifiable projects but not wanting to commit to certification? I have three projects just this week toying with going this route.”

That was the opening salvo in a recent email discussion I was involved in among a group of architects. With the permission of those involved, I’ve anonymously synthesized some of the key takeaways here. I’d also like to hear from you: please post your experiences on LEED certified vs. certifiable projects below.

It’s about the cost, stupid

The following comment summed up some of the objections out there to pursuing LEED: “We are seeing a little green fatigue as well internally and externally; somehow making a project ‘certifiable’ instead of certified seems less onerous and costly.”

Another architect states, “It is important to know what the motivation is behind not pursuing [LEED] certification. Nine times out of ten for my clients it was the cost of certification. I typically respond to them by explaining that the vast majority of the incremental cost is doing the documentation, modeling, etc., which would be necessary to verify goals are being met regardless of LEED. Once the building owners have spent the fee to document performance, perform modeling, etc., the added cost to pay GBCI simply gives them external validation.”

Another architect states, “It is important to know what the motivation is behind not pursuing [LEED] certification. Nine times out of ten for my clients it was the cost of certification. I typically respond to them by explaining that the vast majority of the incremental cost is doing the documentation, modeling, etc., which would be necessary to verify goals are being met regardless of LEED. Once the building owners have spent the fee to document performance, perform modeling, etc., the added cost to pay GBCI simply gives them external validation.”

Another architect agrees on where the cost comes from: “In my experience, documentation is not the largest cost of LEED certification; it's meetings and coordination. These costs would likely be incurred for a certifiable project as well.”

While there was consensus in the group about the marginal cost of actual certification, another person noted one of the counterarguments they hear: “Isn't this just good design? Why do we need to pay extra?” Those questions also arise internally, as an architect reports: “I'm also having to convince our teams. They feel like they don't need it to validate what they are doing.”

The perception of unnecessary spending also came up: “We've seen a client refuse to pursue LEED on their corporate headquarters because they felt it sent the wrong message to their employees. The project would have come out in the high LEED Gold to Platinum range with 30%–35% energy savings, excellent daylighting, aggressive water reduction, good landscaping and stormwater swales, and even a big third-party funded PV system. They were committed to a high-performance building but they felt a plaque was a frivolous gesture.”

Quality control… delivered with a plaque

For most of the architects in this discussion, the cost of LEED was inextricably linked with the quality control it delivers. “I usually talk with [clients] about what costs are involved, being careful to point out that fees to the USGBC are very minor in comparison to the cost of actually implementing sustainable design solutions.

“I then let them know that if they are serious about building green, LEED actually helps them ensure that their project teams deliver. There are so many ways to get off track and not achieve the project goals. By holding the team’s feet to the fire with LEED, I feel we are far more likely to actually achieve these goals. The idea that LEED provides a check for them seems to be eye-opening to most clients with the question.”

“Earning the certification ensures that the goals set in the design are achieved in construction,” says another architect.

“One argument we like to make on the value of LEED certification,” another chimes in, “is that you simply won’t get the same results without the third-party audit—like auditing a class instead of doing the papers and taking the final. The natural tendency will be to let things get lost, not have the same degree of follow-through and rigor. That sometimes works!”

Do we need LEED? A consensus view, voiced by one architect, was that we do: “I’d feel better about not pursuing LEED if I felt there were a true commitment and we had other ways to prove the overall sustainability of the project. But in most cases, I feel if the project loses LEED, they'll lose any hope of a more sustainable project.”

The difference between certified and certifiable

“How do you lose a green building?”, one architect quips. “One VE [value engineering] at a time...."

He explained: “We've had a client who was required by a local agency to pursue LEED as a condition of some public incentive dollars. The client asked if LEED ‘equivalent’ would be acceptable, and was told yes. Later, the agency came back and reversed its earlier position, requiring certification after all.

“In the scramble to document the project after the fact, we learned that low-flush toilets had not been installed, VOC limits were not observed, landscaped area was downsized and would no longer comply.... The list goes on.

Another architect cuts to the quick: “I still love to simply point out that, the whole point of LEED is you are either really doing it or you are not, right? To me there is no such thing as ‘LEED Certifiable.’”

Talking to the client: The Three Questions

How do you talk to clients who have doubts about LEED?

“Where we have had some success,” says one person, “is getting clients to back up a bit before they want to jump into making decisions about LEED. They might say, ‘I want a green building.’ Their natural tendency is to want to then jump to a LEED checklist.” Where we have had more success is that we get them to look at things more philosophically before jumping into some checklist. We call it the Three Questions.

- Who are you? Focus on their organizational Vision, Mission and Culture. People will make and keep decisions based upon their values. I even got a CFO [Chief Financial Officer] to admit that a budget is a value-based tool.

- What are you? An investigation into current practices, that is, institutional knowledge. Not just how their current facilities are built, used, and operated, but how are people trained using their buildings.

- Where do you want to go? Once there is clarity about their values and knowledge, one can then look at means to moving forward. You can set sustainable goals and then show the long-term benefits of using LEED as a tool to guide decision-making and as a means to indicate compliance to their staff and customers.”

Leave the LEED light on

“I tell them that we need to still track and document the project, and LEED Online is the best tool for that, especially regarding the contractor submittals,” says one LEED proponent. “We can then at least start taking them through the process and leave the option open to push the ‘Submit’ button later on in the process. My strategy is to try to leave the LEED door open for as long as possible.”

Along similar lines: “Sometimes if we feel they are just not ready to deal with the added level of complexity of LEED at the initial negotiation phase simply because they don’t want to deal with it, we defer the discussion. Sometime early on within the concept phase we’ll mock up a checklist, show them what they are doing in LEED terms and suggest that if they’re doing all this anyway, why not get it certified?”

Trying to convince them to get the plaque?

Here are a few points that can also support the pro-plaque position:

- Having more experience with LEED certification can give general contractors, subs, and vendors a competitive advantage when they are bidding on future projects.

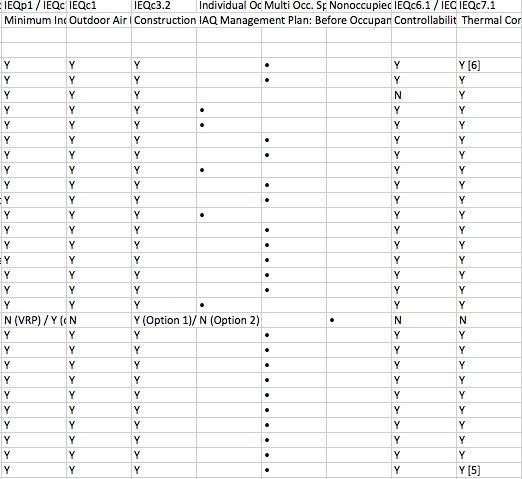

- Some LEED credits lend themselves to being “LEED equivalent” whether you document it or not (there's a green/ white roof or there’s not; rainwater harvesting or not...), but quite a few credits where the design team may not be sure you are “certifiable” without actually doing the documentation tasks: Is the exterior light power density low enough? How much better is the stormwater management? What percentage of your materials really was purchased locally? Is all the paint really low-VOC?

- True, a big part of the cost is documentation, but that can still add value:

- LEED ‘may’ help with quality-assurance/quality-control during bidding and buyout, as there is great scrutiny on what's actually going into the building.

- The attention paid during commissioning and IAQ management may set a higher bar for attention to detail.

- Having LEED criteria may reduce the chances of VE'ing out important items that have a higher first cost but have long-term life-cycle benefits or user-comfort benefits.

What are your experiences in weighing LEED vs. “LEED equivalent”? Please comment below!

The

The

Another architect states, “It is important to know what the motivation is behind not pursuing [LEED] certification. Nine times out of ten for my clients it was the cost of certification. I typically respond to them by explaining that the vast majority of the incremental cost is doing the documentation, modeling, etc., which would be necessary to verify goals are being met regardless of LEED. Once the building owners have spent the fee to document performance, perform modeling, etc., the added cost to pay

Another architect states, “It is important to know what the motivation is behind not pursuing [LEED] certification. Nine times out of ten for my clients it was the cost of certification. I typically respond to them by explaining that the vast majority of the incremental cost is doing the documentation, modeling, etc., which would be necessary to verify goals are being met regardless of LEED. Once the building owners have spent the fee to document performance, perform modeling, etc., the added cost to pay

Add new comment

To post a comment, you need to register for a LEEDuser Basic membership (free) or login to your existing profile.